Practical Bubblewrap

Jan 12, 2026

Table of Contents

- The Problem Why desktop OS security lags behind mobile

- The Solution Introducing Bubblewrap as an enforcement layer

- How It Works A breakdown of Mount, Network, and User namespaces

- Practical Example Building a sandbox from scratch and troubleshooting libraries

- Gotchas Common pitfalls: X11, D-Bus, and special filesystems

- Conclusion Final thoughts on intentional security and Flatpak

'Tis the time's plague when madmen lead the blind.

Do as I bid thee. Or rather, do thy pleasure.

Above the rest, be gone.

The Problem

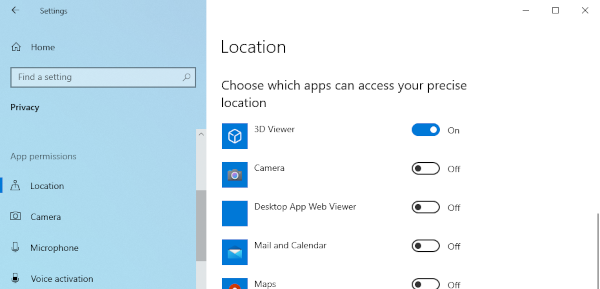

Desktop operating systems were not designed with strong application-level security as a primary concern. For that reason, I firmly believe that mobile operating systems like Android and iOS will always have an advantage in this area. Android, for example, forces developers to explicitly declare what their applications intend to do, such as accessing the network, reading photos, or using the microphone. By making these intentions known up front, the operating system can enforce a clear, declarative permission model in which users can independently allow or deny each capability on a per-app basis.

This kind of structured intent declaration simply does not exist for most desktop applications. "But Andrew," I hear you cry, "Windows has had application permission controls for years!" And that’s true, but the difference is subtle and important. On Windows, the operating system generally does not know what an application might need before it attempts an action. Because of this, Microsoft takes an allow all default approach for application permissions, there is no consolidated API for applications to request permissions from the user like there is on Android.

Linux is plagued by this same problem as well. Traditional desktop applications can attempt to access the filesystem, network, or hardware without declaring those intentions ahead of time. By contrast, on Android, the application must explicitly request each sensitive capability, and the system enforces those constraints at the API level. This intent-driven model is why mobile operating systems have a deny all default and desktops have the insecure opposite.

There are two big reasons you want a declarative intent based policy. Firstly, the obvious case, because it can be enforced that the app must explicitly ask for permission before performing actions, it flags suspicious behavior. Why does my calculator need networking?! Secondly, it protects against runtime vulnerabilities. Good luck doing path traversal on my minimal rootfs.

So just like on Android: the ideal solution would be for both parties to do a handshake of sorts at runtime to say what the program will and will not have access to. The app says I will only use x y and z. And the operating system can say: "Well I'll give you x and y take it or leave it"

If you're a developer and you want to bake intents into your app, they probably do exist for your operating system, they are just not enforced (the problem).

- Linux: seccomp(2) / landlock(7)

- OpenBSD: pledge(2) / unveil(2)

- Windows: AppContainer

The Solution: Bubblewrap

If we want this level of granular control on Linux, we have to stop relying on the

application to "behave" and start enforcing boundaries from the outside. This

is where Bubblewrap (bwrap) comes in. Originally

developed as part of the Project Atomic ecosystem and now a core component of Flatpak,

Bubblewrap is a low-level unprivileged sandboxing tool.

Unlike heavy virtual machines, Bubblewrap uses Linux namespaces to

create a restricted environment. It allows you to pick and choose exactly which parts

of the host system the application can see. If you don't explicitly give an application

access to your ~/Documents folder, as far as that application is concerned,

that folder simply does not exist.

I've heard often the mantra "Monero is what Bitcoin maxis think Bitcoin is." Likewise, "Bubblewrap (security) is what Docker maxis think Docker (security) is." Bubblewrap is thin wrapper around namespaces, a powerful extension to chroots.

How It Works

Bubblewrap works by creating a new execution context and "mounting" only the necessary

filesystems into it. You can think of it as a more secure, flexible version of

chroot. Here are the three primary mechanisms it uses:

-

Mount Namespaces: Isolates the filesystem view. You can provide a

minimal

/usrand/libwhile masking the rest of the drive. - Network Namespaces: Can completely disconnect an application from the internet by simply not providing a physical interface.

- User Namespaces: Allows the application to run as "root" inside the sandbox while remaining a standard, non-privileged user on the actual host system.

A Practical Example

The easiest way to explore a sandbox we make is by running a shell within it, let's make a sandbox for bash to sit inside. We'll restrict it to our home folder.

host$ bwrap \

--ro-bind /bin/bash /bin/bash \

--bind $HOME $HOME \

/bin/bash

bwrap: execvp /bin/bash: No such file or directory

What gives? /bin/bash definitely exists on my host. Really

what this not-so-verbose error means is that the dynamic linker cannot

find the shared libraries bash depends on, because our sandbox has an

empty root filesystem. You can see all of the libraries a program depends

on like so:

host$ ldd /bin/bash

linux-vdso.so.1

libreadline.so.8 => /usr/lib64/libreadline.so.8

libtinfo.so.6 => /usr/lib64/libtinfo.so.6

libc.so.6 => /usr/lib64/libc.so.6

libtinfow.so.6 => /usr/lib64/libtinfow.so.6

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2

Let's explicitly add the libraries it mentions. linux-vdso is a kernel-provided

virtual object, not something loaded from the filesystem, so we don't bind

it. Explicitly binding libraries can get kind of dicey if the paths change. For

less dependency chasing you can just bind entire /lib{,64} directories.

Though, this does obviously have an increased attack surface and bleeds some system info.

host$ bwrap \

--ro-bind /usr/lib64/libreadline.so.8 /usr/lib64/libreadline.so.8 \

--ro-bind /usr/lib64/libtinfo.so.6 /usr/lib64/libtinfo.so.6 \

--ro-bind /usr/lib64/libc.so.6 /usr/lib64/libc.so.6 \

--ro-bind /usr/lib64/libtinfow.so.6 /usr/lib64/libtinfow.so.6 \

--ro-bind /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 \

--ro-bind /bin/bash /bin/bash \

--bind $HOME $HOME \

/bin/bash

bash-5.3$ pwd

/home/andrew

bash-5.3$ echo *

Downloads Music myfile.txt

bash-5.3$ /bin/ls

bash: /bin/ls: No such file or directory

bash-5.3$ cd /

bash-5.3$ echo *

bin home lib64 usr

bash-5.3$ echo $USER

andrewNice, we got a shell and can run some commands. Notice I only used shell built-in commands, that's because we don't have any other binaries! See how tiny that root directory is? It has exactly the directories/files that we bound and nothing more.

Note that in the sandbox we can still see our environment variables are

carried through. You can wipe the environment with --clearenv.

So far we've only restricted the filesystem namespace; we haven't used

bubblewrap to its fullest potential. bubblewrap allows us to unshare specific

namespaces and create a unique one for the process. To do this for all

available namespaces you can do --unshare-all. Let's do this

and liberally bind some other libraries and programs so we have some utilities

to demonstrate the power our sandbox gives us.

host$ bwrap \

--unshare-all \ # Isolate all namespaces (network, PID, user, etc.)

--cap-drop ALL \ # Strip all kernel capabilities (cannot escalate)

--clearenv \ # Wipe host environment variables

--die-with-parent \ # Kills the sandbox if the parent dies

--proc /proc \ # Private /proc required for many tools like 'ps'

--dev /dev \ # Minimal device nodes (null, random, etc.)

--ro-bind /usr /usr \

--ro-bind /lib64 /lib64 \

--ro-bind /bin /bin \

--bind $HOME $HOME \

/bin/bash

bash-5.3$ env

PWD=/home/andrew

SHLVL=1

_=/bin/env

bash-5.3$ ip -o link

1: lo: ...

bash-5.3$ ps -ef | awk '{print $1, $2, $8}'

UID PID CMD

1000 1 bwrap

1000 2 /bin/bash

1000 5 ps

1000 6 awk

Okay so... our environment is gone, our network interfaces are gone, and our

external system processes are gone. Pretty isolated! Note: If your distro

uses a merged-usr setup, ensure you bind the actual /usr directories

and not just the symlinks.

--unshare-all is a macro which runs all the possible namespace

isolation types: see bwrap(1).

Bubblewrap Gotchas

A few other things to be aware of when wrapping your apps:

-

Special files: lots of programs depends on the special

files that the Linux kernel creates like

/dev/random, the/procfilesystem, and the/tmptmpfs. Bubblewrap provides arguments to also create these special files for you. -

X11/Wayland: If you want to run a graphical app, you have to bind

the display server's socket (usually found in

/tmpor/run/user/...). In X11 This creates a hole in the sandbox that a malicious app could potentially exploit to log keystrokes. This is mitigated in Wayland. - D-Bus: Many desktop features (notifications, file pickers) rely on D-Bus. To make these work, you have to allow the sandbox to talk to the system or session bus, which significantly increases the attack surface.

-

DNS:With

--unshare-net, your app is a hermit. Even if you allow network access, you often need to bind /etc/resolv.conf so the app knows how to resolve domain names.

Conclusion

The "deny all" security model of mobile operating systems is undeniably superior, but we don't have to wait for desktop Linux to be rewritten from scratch to enjoy its benefits. Bubblewrap gives the power to take a legacy, "allow all" environment and carve out a high-security niche for the applications which aren't fully trusted.

Is wrapping every single binary in a custom bwrap script practical?

Though it might make sense for some servers—probably not for the average user.

That is why Flatpak provides opinionated bindings and permissions for

each package bringing a more mobile-style permission model to the Linux desktop.

However, for sysadmins and the paranoid, understanding the raw mechanics of Bubblewrap is worth its weight in gold. Whether isolating a web scraper, sandboxing a build process, or just curious as to where a program is reaching on your system, bubblewrap keeps your program in whatever cage you deem fitting.

Desktop security is plagued by its history, but with a bit of intentional plumbing, systems can become a lot more resilient.